Presence in Absence: Chris Reid's Dublin

by Sarah McAuliffe, December 2024

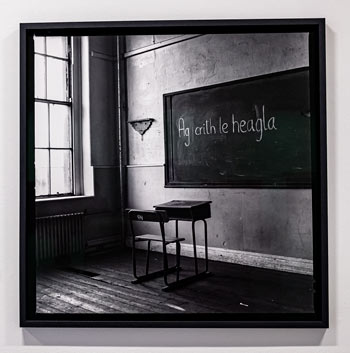

I first encountered Chris Reid's work during the 194th Annual Exhibition at the Royal Hibernian Academy of Arts, Dublin (2024). His photograph Ag crith le heagla (Shaking with fear) completely enthralled me and I found myself returning to it time and again. As the artworks in the Annual Exhibition are not accompanied by explanatory labels, I found myself turning to my own interpretation. I immediately associated the space in this photograph (Fig. 1) – a sparse classroom with a single chair, desk and a blackboard with the haunting words Ag crith le heagla or 'shaking with fear' in English, written on it in chalk. The classroom, long abandoned, dated to the days of corporal punishment and the strong influence of religion in Ireland, which infiltrated a number of institutions, schools among them. There is an overwhelming sense of despair and isolation in this space. The blackboard is crumbling and all but one seat and desk have been removed. The world outside of the window seems out of reach. This work is unpopulated by people, yet I can hear the thumping of hearts, nervous breaths, the scrawl of chalk on the board, and the passage of time measured by the school bell. For me, this empty space has a resounding presence.

Ag crith le heagla belongs to an ongoing project called Site Visits in which Reid relates structures and sites in the built environment of Dublin to his own memories and life experiences.1 Of course, many of the locations and spaces in this series are also evocative in the contexts of local, municipal and broader histories. Most of the structures photographed on each site have either been demolished or have substantially changed over time. Site Visits captures this, and addresses themes of change and impermanence that are universally significant. This project asks how a narrative can be constructed in the face of transformation.

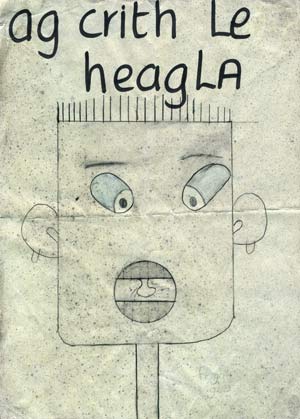

Reid took the photograph Ag crith le heagla in 2015 in a classroom, at an abandoned Christian Brothers school for boys in Dublin's city centre. Reid explains that though he never attended this specific school, it reminded him of those he had as a child in the 1970s - a primary school (for children aged between 4 and 8 years old) and a secondary school (for those aged between 8 and 13 years old). Though there were some desks in this particular classroom, Reid decided to remove them, until one was left. In so doing, this classroom represented memories from Reid's own life, feelings of isolation that are difficult to acknowledge, and thus a solitary desk was all he needed for this picture.2 The text on the blackboard was written by Reid. He found the words 'Ag crith le heagla' written on one of a number of discarded drawings in a corner of the dusty classroom (see Fig.2). These were possibly part of a school exercise from decades past.

The words resonated with him so much that not only did he write them on the blackboard with chalk, he also titled the resulting photograph after them. Reid remembers winter mornings, sitting in a similar classroom, his palms sweaty as the teacher would bark questions at random pupils, testing them on Irish vocabulary and grammar.

He too was shaking with fear. He recalls that when a question was asked and he was selected, it was necessary to answer quickly. If he got the answer right it was a relief but, if he could not answer or got it wrong, he was told to stand at the side of the room until the end of the class, at which point he would be called to the top of the room to be slapped on the hands with a bamboo cane before his peers.

Today, descriptions of such events take on a grotesque quality, but they were everyday reality for the people enduring the abuse and punishment. The experiences and emotions that linger in spaces like that photographed in Ag crith le heagla are palpable in this image and shared by many.

Empty Spaces & Physical Traces

From the moment I saw Ag crith le heagla, I wanted to learn more about Reid's practice as an artist and spent much of the summer of 2024 doing just that, focussing on his output over the last two decades. Through meetings with Reid and a close examination of work across all media, I found myself returning to the idea of "presence in absence", which I believe is most pronounced in his photography. I go right back to a project developed over six months in 2005 – York Street Flats, for which Chris visited a complex of flats on York Street in Dublin City before they were demolished in 2006.3 He photographed the façades of the complex, as well as the interiors of abandoned rooms. The impetus for this project was to document the spaces and history of the flats, as well as commemorating the lives of the people who resided there. The images that make up this series are arresting, both formally and thematically. Viewers are invited into the picture space where time stands still.

There is an eerie sense of someone just having left the room in many of these works. In Room Interior 1 (Fig. 3) a suitcase is abandoned on the highly patterned carpet. Bathed in warm light, it lays there, open. It is as if someone has rushed out of the room without enough time to pack. Or perhaps, they are returning. This is just one of many ideas that a viewer ponders when encountering the photographs in the York Street Flats. Turning to Hearth 1 (Fig. 4.), we are presented with a tiled fireplace, at the base of which is a ceramic sculpture of a man playing guitar, accompanied by a woman in a flamenco dress. Does this statue have a particular meaning for the owner? Is someone coming back to claim it? Or if not, why? These questions pull the viewer into the York Street Flats photographs and suspend them in that moment in time.

In Hearth 4 (Fig. 5), life is ongoing – a walker is left before the hearth, which is populated by cards, religious imagery and family photographs, although the person or people occupying this flat are absent from the scene. Significantly, to the right of the hearth, hangs an open calendar, dating the work. Meanwhile, monographs of artists and musicians are discarded by the fireplace in Hearth 2 (Fig. 6).

The feature of the hearth, unites many of the works in York Street Flats. When considering the physical spaces and social links that sustained the people who lived in these flats, the hearth is of great importance. In Irish culture, the hearth is taken to be the heart of a home, an idea that forms the core of the artworks in this series. Each hearth was individualised by the tenants, from personal selections of wallpaper, paint and tiles to the arrangement of ornaments on the hearth. Indeed, as Katerina Gregos, curator of ev+a 2006 writes:

"A looming sense of loss of a different kind can be found in the photos of Chris Reid, which depict a series of Georgian interiors of houses awaiting demolition. Empty and abandoned, the images speak loudly of lives lived and times changing." 4

The process of vacating the York Street flats commenced some years before Reid's 2005 project.5 Yet, the hearth still shows signs of warmth and offers clues about the people who lived in each space. One could easily assume that these flats were still occupied when viewing these photographs, although this was not the case. Again, a powerful sense of presence pervades these vacant spaces. There is a lingering life force in these works that grips me.

Reid's impulse to document sites and spaces before they are demolished was fundamental to his 2013 project St. Brendan's Mental Hospital. It was announced in 2013 that parts of this hospital in Grangegorman, Dublin were to be demolished once patients were moved out, while other buildings were to be refurbished as part of the development of a new university campus. After the last patient was transferred to Phoenix House, a new institutional building in May 2013, Reid progressed from photographing the façades of the hospital's buildings and its grounds to the interior.6 While all staff and patients had moved out, many traces of them were left behind and can be witnessed in Reid's photographs.

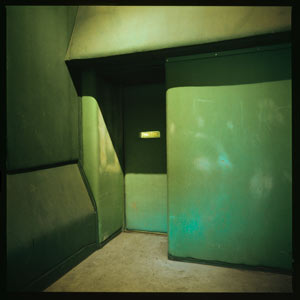

In Padded Cell on the 'Disturbed' Ward' (1/4), the walls of the cubicle are covered in green padding (Fig. 7). Looking closely at the padding, fingerprints, scrawls, marks and dints become apparent and a profound sense of pain, grief and fear is tangible. The people who occupied this space are gone; nevertheless, they can be felt in these imprints.

Similarly, Waiting Room (Fig. 8) traces the many hundreds of people who would have passed through this space, or indeed spent several hours in it. Many features of the waiting room remember the human forms that touched them – over many years, imprints of bodies have altered the shape of the leather chairs lining the walls and the sheen of the floor has dimmed under the weight of trollies, furniture and the hurried feet of the staff. The lights are on, the doors open. It is as if the space has been deserted in a hurry.

In many of the images in this series, such as Patients Possessions and Patients Documents and Belongings (Figs. 9 and 10), the personal effects of previous patients are discarded in piles on the floor or in uncategorised boxes. Physical traces of the both the staff and the patients are discovered here – the actual belongings of those who stayed in the hospital and the records that employees would have recorded about them. One can't help but wonder what will become of these items and documents that are undoubtedly significant to the organisation and personal to the individuals within it, past and present.

The hearth reappears in this body of work with the photograph Bottles of Temazepam and other drugs on a hearth (Fig. 11). Here, rather than witnessing the personal trinkets selected to adorn the hearth, bottles of various medications sit atop the mantle. The vibrant patterned wallpapers often seen around the hearth in the York Street flats surrender to a sickly ochre wall colour here.

Much like Ag crith le heagla and many of the photographs in York Street Flats, an unnerving sense of abandonment pervades the images throughout St. Brendan's Mental Hospital, with subtle traces of those who once inhabited and worked in the rooms and wards. With this series, Reid captures the spatial and physical reality of the hospital and demonstrates that even in uninhabited locations, the impressions left by those no longer there persist – in the spaces themselves and in Reid's photographs.

A number of the buildings depicted in this series were demolished between 2013 and 2014; others were gutted and renovated to fit their new use as part of a university campus. Despite these changes, Reid's photographs faithfully document the physical reality of this place and the vestiges of those who once inhabited it as it existed.

Evocative Words

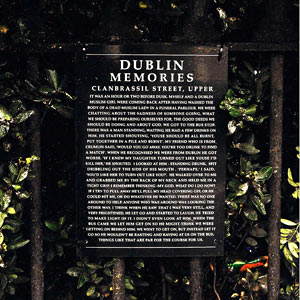

When examining Reid's work, it has become apparent to me that the presence of an unknown individual or group of people is not only evoked by their belongings and personalisation of particular spaces, but so too in their words. Returning to Ag crith le heagla, the sense of being in the space is contained within the furnishings and layout of the classroom, and perhaps most powerfully in the text on the blackboard. Here, the viewer is prompted to wonder who wrote it and to reflect on the circumstances that would have triggered these emotive words. Words and memories are at the core of Reid's project Dublin Memories (2000 – 2002), for which he photographed text-works that mimicked heritage plaques in public spaces in Dublin. Based on interviews conducted by the artist with a broad spectrum of people living in Dublin, across class, race, religion, sexuality, gender and nationality, Reid explored and commemorated the memories that are often articulated as shameful or embarrassing and are regularly repressed.7 Motivated by his own feelings of "toxic shame", experienced in his youth, Reid created a framework to change this narrative with this project, allowing people to speak confidently about their experiences.8

From the recorded interviews, Reid edited the transcripts and created a monument comprising multiple voices that address personal experiences of displacement, marginalisation, anxiety, alienation and shame. Each memory was given the authoritative visual form of a heritage plaque and placed back at the specific place where it originated. Reid then photographed each panel and place. During the time of Reid's NCAD degree show, the plaques were installed on railings around the city. The stories conveyed through the plaques are poignant and relatable to many people, while for others, the memories they bear are eye-opening.

In the context of the Dublin I am acquainted with today, I found Clanbrassil Street, Upper (Fig. 12) to be all too familiar. The text on this plaque describes a racially motived attack of two innocent bystanders waiting for a bus. We can't see the individuals in this work, but can sense their confusion, pain and disappointment. These individuals are with us as we are reading the text on the plaque and taking in the surrounding environment, which appears still and peaceful in direct contrast to the events taking place in and around it. I find Reid's juxtapositions of the text and the locations to be most interesting. The texts relate to and dispute with the locations within which they are positioned.9 With the appearance of heritage or commemorative plaques, the text-works exude a familiarity that lures viewers to them. It is only when they read the text that they realise the work is much more complex. As Professor Declan McGonagle notes in relation to Reid's public projects:

"Reid's art operates in the transactional space between the text and the reader, whoever that is, and on the street it can literally be anybody, and is made and re-made each time it is experienced." 10

In Dublin Memories, Reid places value on the words and voices of the people who he interviewed. There is less of an imperative to photograph the actual people involved, than there is to validate their experiences. With this project, Reid demonstrates how this can be achieved through interactions with sited texts. Again, like in so many of his documentary and public projects, the people and scenarios he references are absent, but are felt in what they choose to leave behind, be it objects or words.

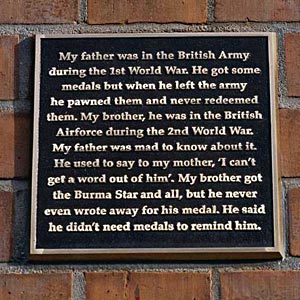

The idea of the plaque and the socio-historical links that it conjures in public spaces was carried into another project – this time, a public art commission, titled Heirlooms & Hand-me-downs (2004 – 2011). This project, commissioned by the Dublin City Council's Public Art Programme, resulted in the production of 21 bronze plaques, as well as a publication about the project and the people involved in it.11 For this project, Reid focussed on an area in Dublin 8 that encompassed Nicholas Street, Ross Road, Bride Street and Bride Road. The distinctive Victorian flats on these roads were due for demolition in the 1990s, but were saved on the grounds of the significance of their architectural heritage to the city. Completed in 1905, many of the people living in them today are descendants of the original tenants. Aware that lived history can be transmitted from generation to generation through stories that trace events, interactions and experiences, Reid set out to record conversations with the residents of the flats between 2004 and 2008 in an effort to generate a micro-history about the area. The oral narratives evolved into a series of 220 short texts, as well as 100 longer anecdotes and stories. Each contributor collaborated with Reid in the final selection of 20 short texts for use on the plaques. These were typeset and individually cast on bronze in the form of commemorative plaques and installed on the walls of the residential buildings in the aforementioned streets. Like Dublin Memories, with this project Reid created artworks based on accounts of the lived experiences of a wide range of individuals in a particular area and then set about placing the resulting oral history back into the community.

The stories conveyed through the plaques are personal, but speak to wider issues and events in Irish society and history. For example, one plaque addresses family planning:

“They had seven children and decided this was enough. One day after mass she arrived home and told her husband that the priest said no one of child-bearing age should stop having children. Sometime later, she had another. Both she and the baby died during the birth. They are buried together”.

This is a small excerpt of a much larger story about the place of the Catholic Church in Irish society and in Irish lives. Others recall the evolving landscape of the area:

“There was a chemical factory across the road. It went up in flames in the 1940s. It blazed for three days. They levelled it and turned it into a car park. My father worked there. Later they built flats on it.”

In another, a resident speaks about the changed behaviour and silence of their brother after his return from war (Fig. 13).

The 21 plaques comprise a permanent sculptural artwork that over time will form another layer to the local heritage. 12

The longer anecdotes and stories were published in a book, Heirlooms & Hand-me-downs: Stories from Nicholas Street, Bride Street, Bride Road and the Rosser, Dublin in 2011, copies of which were distributed to contributors at the launch (Fig. 14).

While, the people who wereinterviewed for this project will eventually pass on and new residents will arrive, their experiences, memories and feelings will live on in their words.

Whether photographing abandoned institutional and domestic spaces, or inserting memories of particular sites and events that took place within these areas through his text-works, Reid brilliantly imbues his art with life and feeling. His photographs and text-works are fully immersive and incite contemplation and reflection. He cleverly individualises the familiar and his projects contain an equally personal and universal appeal. I am never too far away from the classroom of Ag crith le heagla that I first came across in May 2024. From shaking with fear to feelings of nostalgia, frustration and curiosity, I am continuously touched and transported by Reid’s work.

Bibliography

- Cullen, Paul., 'Last tenants vacate York Street ahead of demolition', Irish Times, September 13 2005, https://www.irishtimes.com/news/last-tenants-vacate-york-street-ahead-of-demolition-1.491547

- Curtis, Maurice., The Liberties: A History, The History Press Ireland, Dublin, 2013.

- Reid, Chris., Heirlooms & Hand-me-downs: Stories from Nicholas Street, Bride Street, Bride Road and the Rosser, Dublin, Dublin City Council Arts Office, 2011

- ev+a International – Giveaway, 2006.

- National College of Art & Design (NCAD), Postgraduate Catalogue, 2002.

- The Sculptors Society of Ireland Newsletter, 2002.

- RTE Archives, 'York Street Flats to be demolished 2005',

- The website of Chris Reid: www.chrisreidartist.com

Image Credits

The source of all images used in this essay is Chris Reid, unless otherwise stated. For information about the availability of prints that appear in this essay, please contact Chris Reid.

Author's biography

Sarah McAuliffe is Curator of Irish Art Post 1900 at the National Gallery of Ireland as, where she researches, acquires and displays modern and contemporary Irish art. Prior to this, Sarah was the Curator at the Royal Hibernian Academy of Arts, Dublin (2022 – 2024) where she worked closely with contemporary artists across Ireland and curated multiple exhibitions. Sarah carried out her undergraduate and master's degrees at University College Cork and over the past 10 years has worked in numerous roles in the museum sector, from curating and education programming to marketing and fundraising. Her expertise in Irish and international photography prompted the establishment of a collection of photography for the National Gallery of Ireland, during her time there as Curatorial Fellow (2018 -2021). Sarah worked as a guest lecturer in the History of Art Department at University College Cork between 2018 and 2022. In addition to working with public collections, she researches and sources artworks for private collectors.

Footnotes

- See www.chrisreidartist.com/site_visits.html

- Consultation with Chris Reid, October 2024

- See RTE Archives, 'York Street Flats to be demolished 2005',

- Gregos, Katerina., Giveaway – ev+a International (Ireland), 2006, (catalogue essay), pp.176-179.

- Cullen, Paul., 'Last tenants vacate York Street ahead of demolition', Irish Times, September 13 2005,

- See http://www.chrisreidartist.com/st brendans hospital.html

- National College of Art & Design (NCAD), Postgraduate Catalogue, 2002.

- See www.chrisreidartist.com/dublinmemories_hughlane.html

- The Sculptors Society of Ireland Newsletter, November – December 2002, p.39.

- McGonagle, Professor Declan., 'Figure and Ground: Reflections on the Practice of Chris Reid', Heirlooms & Hand-me-downs: Stories from Nicholas Street, Bride Street, Bride Road and the Rosser, Dublin, Dublin City Council Arts Office, 2011, pp.220-227.

- Reid, Chris., 'A Public History of Community and Place inspired by Private Voice's', Heirlooms & Hand-me-downs, pp.10-15.

- Curtis, Maurice., The Liberties: A History, The History Press Ireland, Dublin, 2013, pp.128-129.