Critical Articles:

Figure and Ground: Reflections on the Practice of Chris Reid

by Professor Declan McGonagle

Chris Reid’s practice as an artist embodies the idea that new forms of art and new procedures are necessary if a new set of relations is to be negotiated and sustained between artist and non-artist. There is a lot of work today which operates under the catch-all headings of socially engaged practice and relational practice which are all qualitatively different from previous ideas of Community Arts. In my view, much of this work is concerned with a representation of those proposed new relations rather than an embodiment of actual relationships in a field of practice. At the same time, we have to acknowledge that not all practitioners or those who mediate in the visual arts recognise that a new set of relations is necessary, or even desirable, and are content with the status quo. This contentment is expressed in not only forms of practice but also in the still dominant forms of distribution. This too is how Chris Reid’s practice challenges inherited ideas of commodity and the setting of the exchange, transaction or negotiation with the non-artist. The traditional idea of the viewer simply does not hold in relation to this work and the intentions behind it.

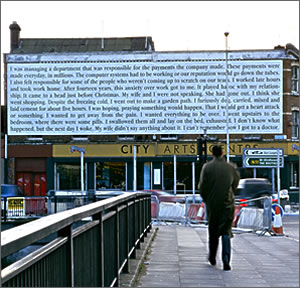

I have come to know Chris Reid’s work through direct experience of projects and through working with him on works in Dublin and Belfast. Typically, these projects use texts based on extensive interviews with people from geographically defined areas or in areas of human activity, with carefully edited sections of text – in some senses a fragment standing for the whole – inserted into public space, on a billboards scale (see fig. 1) or insinuated into public consciousness on a much more intimate scale. This often mimics the sort of heritage signage and historical plaques which mark historical sites and buildings in cities (see fig. 2).

It could almost be described as an art of insinuation. The carriers of the text, and therefore the meaning of the work, are so familiar to ‘a reader’ that their engagement is almost unconscious, until of course the text presents itself as problematic and not as a resolved narrative. Advertising, a power in the public domain, works, as the Irish born media artist Les Levine has said, by creating anxiety and then proposing the means to resolve that anxiety. In Reid’s work anxiety is created quietly but it is left unresolved (see fig. 3). His work is, therefore, not object based at all, although it is carried materially on plaques, signs and familiar information systems on the street. Their very familiarity is part of their effect and their power. Reid’s art operates in the transactional space between the text and the reader, whoever that is, and on the street it can literally be anybody, and is made and re-made each time it is experienced. This is a very powerful model of practice precisely because it works outside of received notions of art production and distribution to include the ‘viewer’ in the making of meaning. Far from being reduced by the process, the location and the procedures developed by Reid, amplify the experience of the art in situ (see fig. 4).

In his most recent project in Dublin 8 the procedure started with the act of knocking on people’s doors and talking to them, not all of whom responded, understood or valued the process, but many did collaborate. In doing so it was interesting how many revealed an inner and outer life – an official and unofficial set of experiences – articulated in a sort of weave of narratives, incidents, memories, dreams and aspirations rolled into a single stream of communication. Our western culture is guilty of understanding history as the collected narratives of the rich and powerful in society. Those whose lives are apparently worth documenting. Many historians over the last two to three decades have projected another reading of history based on the lives of the many rather than the few. We still live in a socio-political media space which celebrates and elevates the rich and powerful as admirable, and one of the measures of that power is also, of course, the capacity to collect works of art as commodities The rich and powerful continue, even in leaner times, to use art to transform wealth into prestige and in doing so create a virtuous circle of attention around themselves.

What this work is really about is value and values. Those who are documented especially in mass media space are valued, but it is interesting that though Reid’s work and strategy also involves documentation, it is not the same in form or intention as a tradition of say black and white documentary photography, which in the 20th century seemed to focus on the many, the street and the marginalised – to the point of cliché. Reid’s documentation confers value on voice and the life as lived, not as observed by a supposedly innocent artist’s eye.

The relationship between subject and object is complex and not at all innocent. In this work the ethical responsibilities of art are foregrounded over it’s aesthetic responsibilities. That is not to say that this work does not have an aesthetic proposition. Everything counts. The point size of the text, the size of the sign, how it is fixed to a wall or railings, how it relates to the field of heritage and information signage are all features considered by the artist and acted upon in different ways in each different situation (see fig. 5). To Chris Reid public space is actually public mind. How and why we see as well as what we see and also what we already know. His interviews draw out from those who take part, extraordinary statements and points of view. A project in Belfast in 2006 involved interviews about the troubles and day to day life in the face of actual or possible violence in areas of the city

(see fig 6).

To have people talk openly demonstrates another dimension of the artist’s practice and that is the issue of time. It is not simply a matter of working slowly and carefully, but how time is one of the key planks of meaning in this practice. Time spent on reconnaissance and research, time spent on establishing contacts, on building trust to an extraordinary degree and also the time it takes to establish more formal supports for the realisation of any specific project. The conversations/interviews which took place were allowed to take their own course. In the Dublin 8 project, the trust, once built up, allowed for an expansive report on a life, and lives lived, in a small number of streets in the Dublin 8 area. This is a kind of history that is not only about the many, it is also owned by the many. It is their possession and in the immediacy of that part of the city, that ownership, still held in common over generations, subverts the usual power relationships which operate in relation to specific parts of Dublin and any city. Too often people from certain identified areas of cities like Dublin, do not participate in the social process, except in certain predetermined marginalised or outsider roles and appear to be eavesdropping even on their own realities. That is the nature of powerlessness. It internalises a disbelief of worth and value in self, in relation to those who have social, cultural and economic power. If Chris Reid’s project is important as a model, it is because of the way it ventilates histories from within, brings them to the surface in public space and proposes that the chosen fragment of an interview – with a sense of voice and place – stand for a whole constellation of narratives that have meaning and value (see fig. 7). These narratives are present universally but are classified by the socio-cultural processes that determine value and worth, which is, in effect, only a reflection of whether those narratives are attached to power – certain kinds of socio-economic power – or held apart from it. Classification is what the traditional model of museum was supposed to do. All human beings, as evidenced in Reid’s texts, make and do things to add value to the quality of their lives. Problems arise only when this making and doing is classified according to pre-defined concepts of value and worth which are then captured and reinforced by a variety of institutional and cultural models.. Chris Reid’s strategic practice cuts across all of these forms of art and institutional production, distribution and validation.

While it clearly helps to have institutional support, his practice is not dependent upon it, yet at the same time he is completely aware of the need to relate to the processes and procedures of the art world in order both to sustain his practice and to ensure distribution of the ideas of another model of practice and another way of negotiating and inhabiting public space. By public space I mean that space which is shared with non-artists. While this can be defined as any public gallery/museum or institutional space, the ultimate challenge lies in negotiating that sharing in a way which does not diminish the practice, or patronise the public who use the space. As a result, when the Chris Reid project is in situ and doing its work it is literally owned by those who have supplied the narratives but also by those who discover the texts and have an immediate experience and construct their own meaning from the work.

Chris Reid’s work confronts Modernism and then by-passes it and operates within another space. It embodies a set of relations, independent of a narrowing debate about Modernism or Post-Modernism which is a constant in group discourse about art and its place in the world. As stated above, there are many who argue art has no role in the world, only in culture. That is a debate which Reid’s work confounds. It is so clearly a product of the world where culture is not something that you possess but something you inhabit and which inhabits you. This is the figure and ground issue. Art history in traditional form has taught us that the Renaissance’s great achievement was the separation of the figure from the byzantine ground and the creation of pictorial space. Representations of that idea of autonomy of the individual and the separation of the figure of the artist from the ground of community or the society is a modernist idea which has occurred throughout human history when the idea that things happen as a result of the actions of man rather than (God) nature, was dominant. The result of this notion developing traction again over the last four hundred years i.e. from the Renaissance recovery of classical (modernist) humanist ideas – is the idea of the artist as a lone genius producer which is only partly being challenged in recent decades by other definitions of value.

What is interesting in relation to this sort of background debate to which Chris Reid as an artist is unavoidably connected is how, when challenging the orthodoxy of figure and ground, embodying a model or figure in the ground, the artist in this case does not surrender his autonomy at all (see fig. 8). He manages to maintain a dynamic tension between his identity as a practitioner and the ground of community and context from which he draws meaning and to which he always returns value. It is this that I am proposing constitutes the innovation in Chris Reid’s practice, not simply the change in material form or the change of location from gallery to street, but the shift in ideology about the nature and purpose of art making, why and for whom it is made in the first place.

Professor Declan McGonagle: Director of the National College of Art & Design, Dublin, Ireland